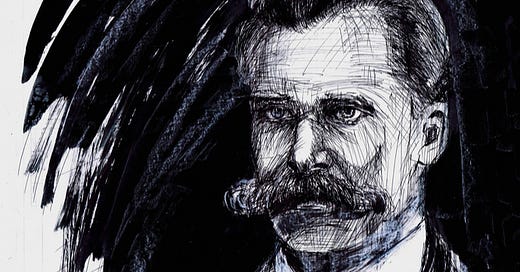

Nietzsche on Modernity

Nietzsche's Critique of Mass Politics and Vietnam's Path to Modernity: A Philosophical Exploration

What does the nineteenth-century German philosopher Nietzsche have to do with Vietnam and its transformation to modernity? Nietzsche lived in the second half of the nineteenth century during the apogee of liberal democracy and industrial capitalism. Modernity, in short, is about two things: first, establishing a republic, and second, initiating the productive forces of capital and labor in the process of production and consumption. For tonight, I'm just interested in the first aspect, which is mass politics and the desire for political equality.

A few days ago I wrote about Liam Kelley, an American historian, and his writing on premodern Vietnamese history as well as the historiography of that history. One of the recurring themes within the writing of Vietnamese history, written either by Vietnamese or foreign scholars, is that they often overemphasize the difference between China and Vietnam. Although Kelley doesn't explain the impetus for this emphasis, it seems to me that this writing of difference stems from the project of modernity, which began in the nineteenth century, that elevates equality as the highest ideal. It is too casual to simply wave off the overemphasis on difference (and identity) as some sort of crude nationalist thinking.

What do we need to do to engage seriously with the fall of dynasties and the rise of the individual, this new political subject that constitutes what is referred to as the masses, the people? And this is where I engage with Nietzsche's work, namely the evaluation of modern politics—mass politics.

In his writing, Nietzsche makes a connection between mass politics and Christianity. The basic argument claims that the death of God left a gap in Europeans' need for salvation. The modern nation-state arrived at the same time to assume that responsibility. Some readers might question whether this claim applies to Vietnam because Vietnam is not a religious country and was never a Christian one, although many Vietnamese converted to Catholicism. However, as we have seen across continents and different cultures, modern mass politics does not need a foundation of Christianity to sprout from.

To say that mass politics reduces individuals to sheep sounds both harsh and elitist. However, back in that century, aristocracy, a political system ruled by talented men (sometimes women as well), still existed, albeit surviving and perhaps even on its last legs, so to speak. Nietzsche's concern about mass politics is that it allows mediocrity to thrive. I speculate that in today's world, he would be critical of mediocre politicians rising to the top, and average men (and women) can say whatever they like, without consequences. Mass politics allows careless speaking because the freedom of speech is one of the pillars of liberal democracy.

Although Nietzsche was a great cultural critic, he missed some of the economic aspects when he analyzed the rise of mass politics. Some say the rise of mass politics and industrial production were twin revolutions, suggesting that liberal democracy and capitalism emerged together, not separately. It was the power of capital and labor that the others of Europe, especially those colonized by them or those forced to open ports for trading, desperately wanted to acquire.

This group included not only well-known countries like Japan and China, but also Vietnam. For agrarian societies like Vietnam, having families of farmers as the sole economic foundation would not be sufficient for empowering the state. More, as the world entered the twentieth century, dynasties around Vietnam fell. Dynastic governance, one led by the emperor, the imperial family, and the class of scholar-officials was no longer the most effective way to rule. The time of mass politics had arrived in Vietnam. Mass politics aimed to bring the concept of 'the people' to life. This new political life required individuals to submit to one nation and speak one language.

Nietzsche's writing is critical of mass politics because it elevated and forced equality as a moral destiny. In other words, we all should be striving for equality. However, Nietzsche argues that forced equality leads to mediocrity. So, instead of an aristocracy ruled by the best, we have a mediocracy ruled by the average or middle-class folks. Just to sidestep a little bit, this mass politics is common across continents and cultural spaces, from India to the United States. So, when politicians and scholars write about the rise or decline of the middle class, they are operating on this very register of morality.

But some readers will ask isn't modern Vietnam, officially known as the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, a one-party state? It is not like the U.S. It doesn't have multi-party elections. Without going into great detail for now, it seems to me this distinction is more technical than general within the view of political philosophy, which I'm aiming to discuss here, not to say there aren't any meaningful and practical differences between a one-party Communist-led state and a multi-party one.

Symbolically, Vietnam is a republic, which means that it strives to be a modern state consisting of individuals who form the people. Not unlike their European counterparts, these individuals must possess self-determination and historical consciousness. Without this historical knowledge, the republic cannot be sustained. Unlike previous histories that were about the imperial families, this new history would be about the masses of individuals and the republic in which they rule.

If we allow ourselves to be entertained by Nietzsche's thesis on mass politics—the claim that modern republics produce herd-like instinct and mediocrity—a condition perhaps worse than death presents itself. It seems that when man decided to forgo his individuality to be part of the masses, he saved his life but lost something conceivably greater.

Paradoxically, one of the things that this new individual, the modern man, desires is complete freedom—obliterating anything identified as external and foreign and dependent. Rather than thinking of freedom, he thinks in freedom—in the eternal prison of freedom.

N.T.D. 12/9/2024