Given the global configuration based on distinct nations and ethnicities, what does Vietnam need to do to relearn its past, particularly its engagement with literary Sinitic, also known in English as “classical Chinese”? And why should we us literary Sinitic rather than classical Chinese?

According to some scholars, this choice is intended to avoid the term Chinese and associated racial or ethnic connotations:

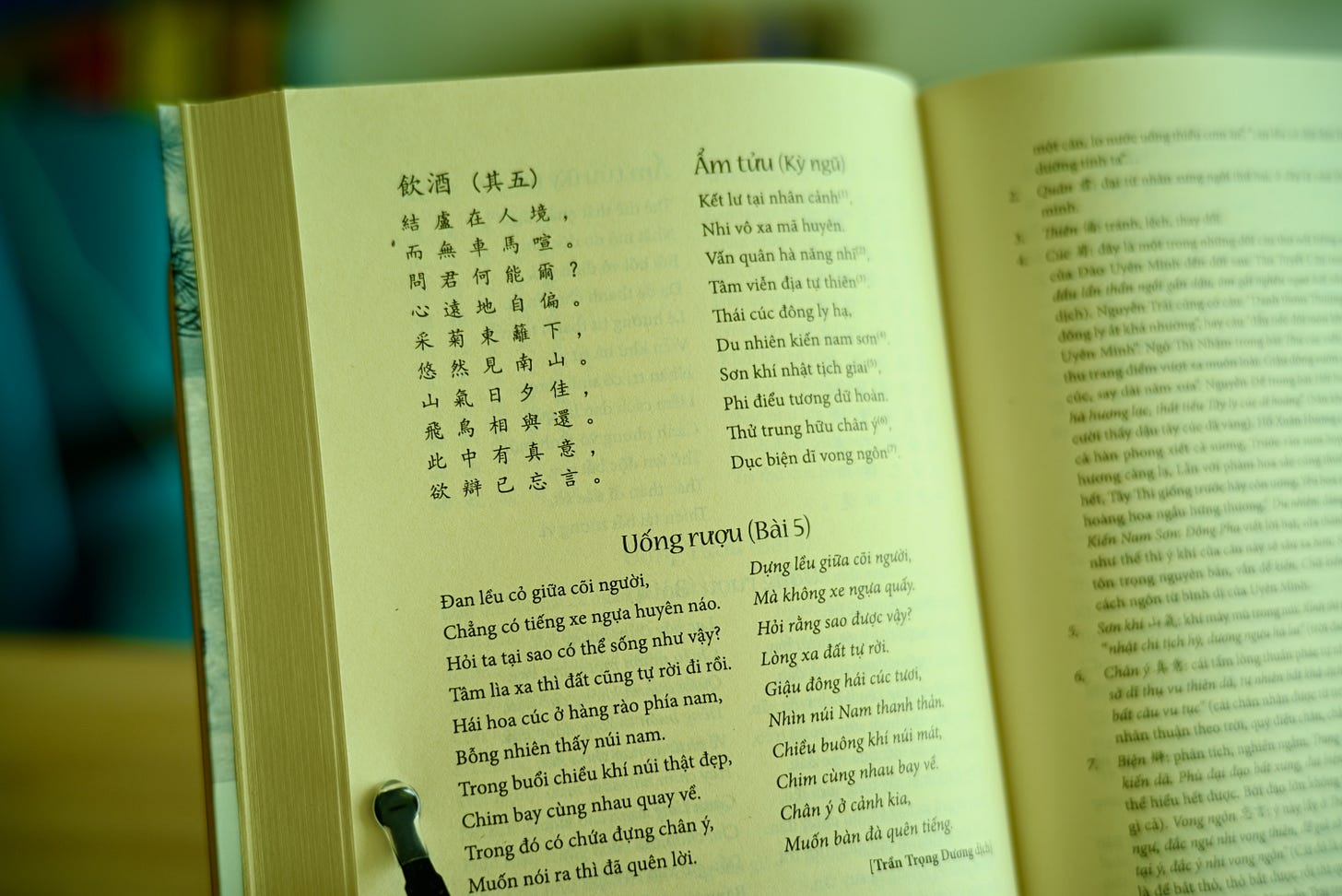

The greatest intellectual threat facing students of East Asia today is no longer eurocentrism (though it is still an intractable problem), but sinocentrism. Thus, we use “Literary Sinitic” to refer to what is called kanbun in Japanese, hanmun in Korean, and hán văn in Vietnamese, and to what in modern Mandarin Chinese is typically called wenyan(wen) 文言(文). - from Literary Sinitic and East Asia: A Cultural Sphere of Vernacular Reading (2021)

In modern Vietnamese, literary Sinitic can be represented as hán văn, and Sinographs (Chinese/Han characters) as chữ Nho. This terminology does not deny the centrality of China or the origins of the writing system. This is more of a compromise between the cosmopolitanism of the past and particularism of the present.

Given that Vietnam’s journey toward becoming a modern nation-state was more or less completed with the conclusion of the Vietnam War, perhaps the time is ripe to reassess Sino-Vietnamese relations. One of the most important shared aspects between premodern China and Vietnam is their shared understanding and use of literary Sinitic.

Contemporary Vietnamese scholar of Hán-Nôm, Trần Trọng Dương, in an interview, described how he first encountered literary Sinitic:

Tôi gần như không có ý niệm gì về Hán Nôm khi còn đi học. Chỉ biết, từ nhỏ, đi học trên những con đường làng lát gạch cũ kĩ và trơn trượt những ngày mưa, tôi vẫn thường thấy những câu đối Hán Nôm đắp vữa ở cổng các căn nhà, và đình chùa miếu mạo quanh trường.

I had almost no notion of Han Nom when I was in school. I only remember, from when I was young, walking to school on old brick village roads that became slippery on rainy days, I would often see Han Nom parallel sentences plastered on the gates of houses, and on communal houses, pagodas, and temples around the school.

It seems to me that this initial encounter—stumbling upon literary Sinitic, something not uncommon in many parts of Vietnam—had a profound effect on the scholar.

Vào ngành Hán Nôm cái là tôi lao đầu vào học, học như chết đói, vì lần đầu thấy việc “chiếm đoạt” một thứ kiến thức cổ xưa, đã gần như không còn mấy người ngày nay biết đến, nó kích thích như thế nào. Cái khát ngưỡng “thoát khỏi” cái cảnh “mù chữ” khi đi vào đình chùa nó thôi thúc mạnh lắm, chỉ biết là học thôi, chẳng nghĩ sau này sẽ làm nghề gì, và nghề Hán Nôm nó sẽ như thế nào.

When I entered the field of Han Nom, I threw myself into studying, studying as if I were starving, because for the first time I experienced how stimulating it was to “appropriate” this ancient knowledge that hardly anyone knows about nowadays. The yearning to “escape” from being “illiterate” when entering temples and communal houses was a powerful motivation—I just knew I had to study, without thinking about what career I would pursue later, or what a career in Han Nom would be like.

Anyone who has visited Vietnam, especially the north, can easily stumbled upon literary Sinitic writings left behind in the various temples and communal houses. And as far as I know, no new literary Sinitic inscriptions have been created—at least in public places—since the middle of the twentieth century. As Trần Trọng Dương (TTD) mentioned in the interview, literary Sinitic is now a lost language in contemporary Vietnam, no one really knows how to read and understand it. However, unlike the Vietnamese living overseas, those living in Vietnam have the opportunity to rediscover literary Sinitic as part of their own cultural heritage.

For Vietnamese like TTD, why is it necessary to appropriate literary Sinitic? Why can’t they just simply learn and use it? One appropriates something when one does not have it—that is to take something for one’s own use, without the owner’s permission. I think it has to do with how modern Vietnamese see themselves, see others. Unlike premodern Vietnamese who simply took the literary Sinitic as a writing system (not their own or someone’s else), modern Vietnamese are obsessed with ownership and do not believe literary Sinitic is their own, regardless of the numerous historical remnants existing in architecture and text, because it is widely considered as belonging to China, a foreign country.

When I read the term chiếm đoạt—to appropriate—it reminded of James Baldwin, the great Black American writer of the Civil Rights Movement. In his autobiography, he writes:

I know, in any case, that the most crucial time in my own development came when I was forced to recognize that I was a kind of bastard of the West; when I followed the line of my past I did not find myself in Europe but in Africa. And this meant that in some subtle way, in a really profound way, I brought to Shakespeare, Bach, Rembrandt, to the stones of Paris, to the cathedral at Chartres, and to the Empire State Building, a special attitude. These were not really my creations, they did not contain my history; I might search in them in vain forever for any reflection of myself. I was an interloper; this was not my heritage. At the same time I had no other heritage which I could possibly hope to use—I had certainly been unfitted for the jungle or the tribe. I would have to appropriate these white centuries, I would have to make them mine—I would have to accept my special attitude, my special place in this scheme—otherwise I would have no place in any scheme.

There are crucial differences between TTD and Baldwin. Black Americans like Baldwin suffered under European colonialism and American slavery system in ways that left them unable to see themselves as belonging anywhere but the West. For the Vietnamese, it is as if they had suffered the same racial oppression against the Chinese. For the Vietnamese, their historical experience with China, while complex, cannot be equated with European domination of the Others of Europe. No records suggest that the Chinese enslaved the Vietnamese, and any argument that Sino-Vietnamese relations were analogous to French colonial rule in Indochina during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries is indefensible.

One of the most important issues facing Asia in the twenty-first century is not Westernization, at least not directly. What is indirectly manifesting, however, is the persistent use of Western concepts—such as race and ethnicity—as defining features of human groups, and the acceptance of the idea that race/ethnicity maps directly to culture and language. Fringe notions such as Han or Việt supremacy do surface from time to time but do not define the actual policies of China or Vietnam. But these racial ideas unmistakably stem from nineteenth-century scientific tools of European colonialism and imperialism.

When we read modern accounts of Sino-Vietnamese relations, the main thesis is that the Vietnamese have always existed as a distinct people and that China repeatedly sought to suppress Vietnamese independence. In other words, the racial/ethnic conflict has always existed between China and Vietnam, and that Sino-Vietnamese relations is not different than let’s say, between black and white, or between French and Vietnamese. Consequently, literary Sinitic when represented as classical Chinese is a remnant of historical Chinese domination and Vietnamese dependency.

If Baldwin wants to “appropriate these white centuries” in order to reconcile with the past, the Vietnamese also believe that they need to appropriate “the Chinese centuries”, the so-called Chinese period, “the period of Chinese rule” (thời Bắc thuộc), dated from 111 BC to 939 AD.

However, what if the Vietnamese moved beyond this binary opposition and instead saw Sinitic culture, as expressed through literary Sinitic, as their own (not something imported from the outside and now have to be appropriated)—In this view, the parallel sentences that are engraved into the wooden columns have always been a part of their identity.

For Black Americans like Baldwin who faced centuries of modern racial oppression but having nowhere else to go, the idea of appropriation makes sense. However, the Vietnamese (as well as others) have often deployed the concept of racial/ethnic conflict when trying to understand Sino-Vietnamese relations. It seems to me the purpose is not to understand the premodern history between China and Vietnam, but to appropriate the racial concept—establishing moral and intellectual distinctions—in order to make sense of a radically new world order, one that saw European nations conquered the world.

How might someone born in Vietnam after the twentieth century imagine literary Sinitic as their own writing, culture, and identity? It is evident that the Western model of nation states is here to stay. How can Vietnam maintain its distinctiveness, especially given the rise of modern China? Can the Vietnamese, like Trần Trọng Dương, appropriate literary Sinitic—taking it as their own? And for the rest of the twentieth-first century, can they move further to simply treat literary Sinitic as their own?